Clinton Hill, by Susan Larson, Ph.D.

I

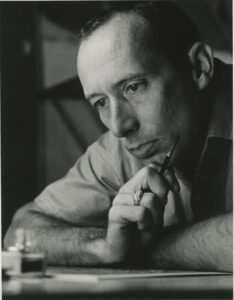

Clinton Hill (1922-2003) was an avid and fearless traveler. Traversing the globe, he pursued life’s many sights, intense flavors, colors and bright sounds. Born on a ranch in rural Idaho, he was a child of the American West with the tall, rangy, easy-going good looks of one who could, and did, spend time as an actor on the stage. The boundless vistas of his Idaho home and his early exposure to native American people and culture, imprinted his character with a natural expansiveness and the gift of a warm and open heart. Slow to judge, quick to find common ground, he was the ideal traveler, a seeker who expected surprise and delight around every bend of life’s unpredictable road.

In the autumn of 1956, young Clinton Hill stood beneath the entrance of the Friday Mosque at Fatehpur Sikri in India, while traveling on his year-long Fulbright grant. In his traveler’s journal we find the inscription he saw over the ornately decorated entrance to that enormous and historically significant mosque. Attributed to Jesus, it was part of the ecumenical program of 16th century Mughal ruler, Akbar the Great. « The world is a bridge, use it. But build no houses upon it. He who hopes for a day may hope for eternity; but the world endures but an hour. »

Then twenty-four-year-old Clinton Hill had already shown his work in New York City to critical acclaim. His important friends predicted a brilliant future for him. Hill chose to traverse that bridge, to embrace a wider view of the human story. He would then bring its riches into the very heart of his artistic enterprise. Hill would absent himself from the critical cauldron of the New York School in the late 1950s. While in India, he asserted, « Beauty is a source of delight but not an end in itself. It is a summons to action. »

Clinton Hill’s artistic career would continue to prosper for fifty years from the mid-1950s to 2003, propelled by his need for continuous action and episodic change. Intelligent critics would always find the continuity in his work, in his richly intense color, in Hill’s deft exploration materials. A passionate colorist, his work would always be beautiful. But his restless curiosity would draw into the work a world of disparate materials: paper, wood, fragments found on the street, printed surfaces, plastics, letters, numbers, names of places, records and memories all offering invitations to explore anew.

Clinton Hill had dear friends among the artists of the Fluxus movement. Jay DeFeo, Wally Hedrich and George Maciunas kept up a lively correspondence and often used Hill’s New York loft asahome-away-from-home. Their love for fragile yet enduring works on paper found a place in Clinton Hill’s life and art. Yet he was not one of them. Despite his enjoyment of discovery and surprise, Hill created a very complete, elegantly wrought and satisfying body of work that stands on its own as an artistic statement from a highly individual voice.

Moving, fluid, always aware of time passing into memory, his art focused upon the actions of his human hand as the artist teased form out of seemingly fragile and complete surfaces. Following on the generation of boldly expansive action painters, Hill espoused patient observation and an attentive, sometimes playful interaction with his materials and his environment. Hill’s gossamer touch, his torn edges, his delicately dissected surfaces made by ripping and peeling all speak of a sensibility that was gentle, sometimes obsessive, yet strong. His art has an eloquent pathos, a beauty born of naked vulnerability treated with a lover’s reverence.

His was a kind of self-assertion that maintained a warm regard for other presences and voices. He swept a lifetime of loves and enthusiasms into his art. With these exhibitions, held simultaneously, we wish to offer a few of Clinton Hill’s notable explorations along with a preliminary account of his life and career. In the few years since his passing, his artistic estate has yielded many surprises. Known for his wood constructions and large compositions with glowing handmade paper, Clinton Hill was a prominent artist in New York during the 1980s and 1990s until his death in 2003. He had other moments in the spotlight. We now understand how and why these were so significant at the time. His abstract paintings, collages and prints from the 1950s enjoyed a high regard in New York during that historic moment of international prominence and impending change. Clinton Hill’s paintings and constructed works on paper of the 1960s have a dynamism, an exquisite technical virtuosity and originality that adds another voice to the minimalist materiality of that era. His travel paintings and beautiful drawings reflect the warm human being we loved during his lifetime. We are getting to know the full range of Hill’s achievement and we are moved and astonished by its depth and consequence.

II

Clinton Hill grew up on a ranch in Payette, Idaho near the Oregon border. Family photographs show him astride his horse checking the fences and gathering livestock. He is tall, handsome and very capable. Nearby native American settlements attracted his early curiosity and attention. Throughout his life, Hill would wear native American ornaments and talismans, reminders of days spent in the open air in the company of people living close to the land.

When Hill was in high school, his family moved to La Grande, a town in the northeastern corner of the state. At the age of eighteen he earned a private pilot’s license and flew a single engine LAND 0-80 H.P. In La Grande, Hill began his first tentative explorations in watercolor. This led him to Eastern Oregon College (1940- 42) and to the University of Oregon in Eugene (1942-43).

Clinton Hill volunteered for the United States Navy in late 1942 and received a call-up in July of 1943. He would spend almost four years on active duty. While studying navigation, sonar electronics and aeronautics he took art classes at Park College in Missouri and Columbia University in New York City. The navy promoted Clinton Hill to positions of great responsibility and honor, but he always knew that he would leave to become an artist at the war’s conclusion. His inner knowledge also confirmed that he was gay although he fit within life in the Navy and achieved the rank of lieutenant earning two stars and numerous commendations.

By 1944, at the climax of World War II, Clinton Hill was serving as commander of a submarine chaser in the south Pacific. With hundreds of sailors under his watch, Hill and his men patrolled the Pacific hunting enemy submarines. They mapped mine fields and traveled to remote islands. Hill’s ship went to Shanghai as soon as the surrender was signed and his men liberated Chinese prisoners of war while tending to civilians as well. All of this required the technical skills he had acquired in school but most of all, demanded human understanding and his ability to maintain the health and morale of his men in the midst of unspeakable horror. Surviving photographs show Clinton Hill in full officer dress on the deck of his ship surrounded by an orderly cadre of sailors who survived the war unscathed. Among the, enlisted men was Allen Tran who would become Clinton’s beloved partner for the next fifty years.

Clinton and Allen would always be proud of their military service but they looked forward to travel and study at the war’s end. They settled in New York’s West Village in the late 1940s. Clinton Hill attended the Brooklyn Museum School from 1949 to 1951. He studied with German expressionist painter Max Beckmann and New Yorker John Ferren among others. Of great importance to Hill was the classroom of Vincent Longo devoted to the art of the contemporary woodcut. Hill’s colored woodcuts of the late 1940s and 1950s are the first works of distinction and lasting value of his young career. He won a Brooklyn Museum prize and a work went into the museum’s prestigious collection.

Clinton Hill’s paintings of the 1950s build upon the expressionist language of the New York School but with a lyricism and gentle sensuality uniquely expressive of the artist’s character. Hill built each work upon a loosely geometric foundation. Abstract yet suggestive of objects in the world, they feature screens of upright verticals, parallel tracks and windows. He used reds, black and browns, intense smoky colors to soften his insistent geometry. In the summer of 1954, Clinton Hill joined the Korman Gallery in New York City. He took part in a group show that included painters Pat Adams, John Grillo, Angelo Ippolito, Lester Johnson, Alex Katz, Vincent Longo and Philip Pearlstein. Located at 835 Fifth Avenue, the gallery belonged to Marvin Korman, a young man in graduate school at the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University.

The following autumn, Virginia Zabriskie, a fellow student at the Institute bought Korman’s lease for one dollar and established her own gallery. It thrived in several subsequent locations from 1954 to 2011. Clinton Hill became a leading artist in the new Zabriskie Gallery. He had his first oneperson show in 1955. Its title, « Ladders and Windows » arose out of very astute observations made by Hill’s friend, the painter Mark Rothko who saw vestiges of windows, walls, screens and ladders within the dense painterly surfaces of Hill’s early canvases. It was a highly successful debut and led to decades of exhibitions and critical acclaim while maintaining his affiliation with the Zabriskie Gallery.

Hill’s paintings of the later 1950s are grander in scale and more radiant in color. His structures loosened up and allowed the pigments to soar and drift over his articulated but open and airy surfaces. Clinton Hill was finding his artistic voice, something fresh and warm, sophisticated and tender in his appreciation for color and form. These paintings are worlds apart from the brooding, sometimes violent and questioning works of the first generation of the New York School. Clinton Hill’s canvases of the late 1950s are affirmations of the beautiful possibilities of painting in the postwar era when stress and doubt gave way to lyricism and a spirit of powerful optimism.

Yet Hill was a veteran who had seen the worst the world had to offer. Finding his personal identity in the midst of a conservative upbringing had made him strong and also compassionate. He had been to Europe and studied art in the world’s capitals, but he wanted to search further, to see other aspects of the human story. He applied for and won a Fulbright grant to spend a year in India where he hoped to find a broader more comprehensive understanding of man and art than mere national boundaries could offer. He went in the late summer of 1956 and toured many of the famous cultural monuments while lingering over textiles in the bazaars and observing the colorful costumes and festivals in the streets. His diaries and postcards reveal a kaleidoscopic experience, partly philosophical and intensely visual. Tall, slender, with blond hair, he must have stood out amidst the crowds. Yet he moved easily among the people there who sensed his quiet good will and sincere interest in their lives and cultural achievements. He came back refreshed and in possession of new enthusiasms for paper textiles and handmade objects created out of fragile materials vibrant with color.

A wonderful group of collage compositions arose from the year in India. They feature torn and distressed papers. Tickets names of placed visited and colors found on the streets. Clinton Hill developed an original category of works he called “Travel Art” to accompany him on his itinerary. He reasoned that hotels, especially hotels frequented by poor art students, would have terrible art or not art at all. Once simply cannot exist without beauty on a daily basis. So it was essential to bring along and create en route a small quantity of works securely fastened to a traveling folder, which could be displayed and enjoyed in any environment. He would continue making “Travel Art” for the rest of his life.

Upon returning to America, Hill went immediately to Eugene, Oregon to tend to his seriously ill mother. He stayed with her for several years, moving them between Oregon and a house the family owned in Phoenix, Arizona. It was a painful time of being separated from Allen Tran. Hill observed in a letter, « Good is kind suffering, » perhaps referring to his desire to be responsible while also maintaining his own life, love and career. While in Phoenix he responded to the unique colors and textures of the desert landscape in works such as Desert Nagascape (1959) and Desert Germination 2 (1959). These are richly painted collages with elegantly cut wedges of painted paper. The describe a fertile yet arid landscape filled with nature’s energy. He spent time studying petroglyphs in the desert and collected pottery and baskets at the Klamath Indian Reservation in Jefferson, Arizona.

Clinton Hill’s Phoenix sojourn had another surprising and interesting dimension. He embarked upon a semi-serious career as a singer and performer. Hill’s strong tenor voice and his elegant stage presence landed him a spot in the Phoenix Men’s Chorus then parts in the Phoenix Civic Light Opera where is appeared in “The Merry Widow,” and “Die Fledermaus” and other productions. He appeared in “Damn Yankees” in 1958 and sang in a 1959 “Pops Concert” he performed Mozart, Schubert, Puccini and Verdi arias. In the autumn of 1959, he appeared with the Scottsdale Chamber Opera as both singer and designer of the production.

Hill might have stayed in Phoenix where he was warmly received by the artistic community and by the Phoenix Art Museum. He participated in their annual exhibitions during the late 1950s and early 1960s. But the pull of New York and his relationship with Allen Tran led him back to the city by 1962. Hill and Tran had navigated the unsteady paths of their family relationships by this time, and they decided once more to establish their own household together. Allen Tran observed in a letter to Clinton of 1959, « Once man becomes acceptable to himself, the need for acceptance by others will vanish. » Their home and studio became a haven for others passing. through New York from the West Coast and Europe. Jay DeFeo often stayed with Clinton and Allen on her trips to New York. She wrote frequently and embellished her communications with drawings, diagrams and news of her life and art. George Maciunas, a key figure of the Flux us movement, was also a friend. Clinton Hill’s great appreciation for works on paper made him an enthusiastic audience for everything that was brilliantly ephemeral, theatrical and new.

III

Clinton Hill’s handsome and incredibly complete body of work from the 1960s has recently come to light. Pursuing a strongly geometric vision, Hill sought to endow it with the sensations of speed and motion. He introduced dramatic counterweights, spatial shifts and sharp contrasts of light and color. Grasped all-at-once, they have the graphic strength and coloristic impact typical of the best American art of the 1960s. Some of this work suggests the feeling of running toward a distant place while adjusting for the uneven surfaces of the earth. In others, we soar into a colored ether while remaining conscious of and related to the central axis of our planet. Others have a prescient quietude, a sensation of slowly unfolding like the leaves of a plant in spring or the wings of a juvenile moth.

Over many years, Hill explored the way edges define states of movement, stasis, permanence or fading away into space. He discovered the expressive power of torn edges testifying to the touch of a human hand and the unpredictable action of a gesture at a given moment in time. He had such respect for the material integrity of paper that he sought out those whose long graceful fibers or short blunt ones that would add new voices to the interplay of his art.

At first, one may not even know that his dynamic compositions on paper contain elements of collage. These appear to be small paintings exploring the touch of the brush, now transparent, then loaded with pigment and opaque. But some of the elements are neatly fitted paper wedges placed adjacent to painted shapes so that they merge into the overall image without a murmur. By the 1960s, Hill’s technical command of paper collage had become so deft and sure that paper became a vehicle for achieving his potent imagery and not an end in itself.

Clinton Hill’s work of the 1960s is so disciplined, continuous and clear that it must have had an intellectual component. He was teaching at The City University of New York and was responsible for his students’ artistic and intellectual development as well as his own. Hill’s sketchbooks contain passages descriptive of his swift-moving colored geometry of the 1960s. He outlines three states of balance: axial, radial and occult.

“Axial Balance: Control of opposing attractions.”

« Radial Balance: Control of opposing attractions by rotating around a central point. May be a positive spot in the pattern or an empty space. »

« Occult Balance: Control of opposing attractions through a felt equality between the parts of a field. Has neither explicit axes nor central points. There are no rules for occult balance. »

In the 1960s, many American artists worked with issues centering around actual and perceived states of compositional balance. Californian John McLaughlin and New Yorker Frank Stella explored actual and perceived balance in their work. A distinction is immediately apparent in Clinton Hill’s work of the same period. Hill instilled his paintings and collages of the period with a strong sense of spatial movement. taking his work beyond the closed realm of composition in painting. His work engages with the dynamic physicality of the world and establishes psychomotor interplay with the human eye and mind. Hill said he was very aware of this aspect in his art: « It points up the close relationship between the problems of balance and movement… balance determined by weight and direction. » One might also add color and density as strong elements helping to determine weight and balance.

During this very period. the seminal work of the Russian avant-garde began to appear in the West Exhibitions in Europe and New York drawn from formerly hidden and secret sources allowed artists. historians and collectors to see the radicality, the depth and the brilliance of artists such as Malevich, Tatlin, Popova, Lissitzky and many others. Clinton Hill’s canvases of the 1960s often evoke the evanescent metaphysical spaces, the imagined-some say spiritual – shifting and disappearing planes of the Russian avant-garde. In Clinton Hill’s wonderful paintings and paper compositions, the planes of space sliding into colored ether are loosely tethered to shapes edges and places we customarily experience on earth. His is an achievement too long in storage and unknown to us. Today we can begin to see how well reasoned, we imagined and bold a series of works he created in that innovative and turbulent time.

IV

Clinton Hill began a period of intense collaborative activity in the 1970s centered around his love of paper as an artistic medium. Building upon his early collages, « Travel Art » and his minimalist paintings and constructed drawings of the late 1960s, he began a beautiful series of minimalist artist’s books. Using lush. thick textured paper, Hill gently peeled back strips to open up vents and holes in their surfaces. His tearing, cutting and peeling became a personal form of mark-making. He added bright color in unexpected ways. The effect is to bring the viewer up close to the surface to investigate the expressive tears and marks, then suddenly push one back, almost startled, by the sudden presence of a spot or a shape in radiant color. Hill incorporated delicate strips of cloth, colored strings and fiberglass sheets, building his surfaces so that they would admit light and reflect it to enrich his surfaces. By the later 1970s he had created a group of masterworks Book (1976) Windows (1977) and Tracer (1978) in small editions bound beautifully and elegantly in black linen.

Hill met paper makers John and Kathleen Koller in 1974. John Koller had been working with Ken Tyler on paper projects for Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly Richard Serra, Frank Stella and many others. A fond friendship ensued and Hill often spent time at the Koller’s Studio and workshop in Woodstock Valley, Connecticut. Their business HMP (Hand Made Paper) provided sheet papers to artist and printers. They agreed to collaborate with but a few artists, Hill among them. Theirs was a friendship that would last for decades.

Recent studies of Clinton Hill’s artistic estate have yielded remarkable works from the 1970s revealing the extent of his explorations with paper, fabric and unusual modern materials. He embraced new industrial surfaces and applied his careful, almost surgical skill in peeling, tearing and scoring to their smooth glossy skins. His ink marks have an expressive delicacy. They seem to exist as a reminder of the artist’s presence rather than a declaration of his personality. He coaxed expressive voices out of materials and handled them with a rare sensitivity. Hill. Agreed with John Koller’s assessment. agreed Perhaps with most John noteworthy Koller’s of assessment paper’s qualities is what might be called its humility – in the sense of quiet service…”

Hill became a celebrity as the role of handmade paper in contemporary art became a prominent feature in the late 1970s ideas and early 1980s His virtuosity, unique method and ideas and workmanlike seriousness distinguished him from many others who adopted handmade paper as a convenient and beautiful medium. Artisan paper makers loved Clinton Hill because he so completely entered into the process and community, honored their skill and aesthetic sensibilities and fulfilled their potential through his work.

Hill’s sensitivity to the physical structure of paper led him to create a group of softly minimal works, white on white, with very subtle marks and tears delicately interrupting the surfaces. They are whisper quiet yet intense and serious. These found favor with people who already understood the history and traditions of paper in Eastern and Western art. At other times, Hill’s comfort zone in the paper atelier was such that he could be playful. One day he took Allen Tran’s white linen shirt, tore it into two almost equal parts, then embedded it within layers of white handmade paper. Today it is a poignant tribute to their fifty-year relationship and a sign of the love and fun they shared.

By the early 1980s, Clinton Hill shifted from the delicate intimacy of his previous body of work to a bold new statement in a group of large assembled paper compositions. His technical skills found new expression. He used highly saturated fluid pulp over layers of structured paper so strong that it accepted the weight, texture and water laid on top in multiple layers. Melting into one another, his colors because even more intense, varied and bright. Hill devised stencils to contain areas of color, keeping the structural elements of his composition crisp, clear and bold. Some of the largest works contain no fewer than ten separate sheets working together to create a single image. They are grand in scale, able to speak across the length of a large gallery or a vast public space. Clinton Hill used size itself to create something of the intimacy and detail that had been so typical of his work through the years. In 1981, critic and art historian Martica Sawin aptly described Hill’s work as having a “Track, speeding and looping across and indeterminate field.”

Many of Clinton Hill’s large constructed paper works have several track and arcs moving swiftly form one colored plane to another. With so many tilted, curved and diagonal elements, Hill called into play his sophisticated understanding of states of balance. Some paper constructions feature a dominant, steadying horizontal. Others sail across space relying upon or innate, Hill would say occult, ability to achieve balance while in motion. At times, his paper elements seem to be tumbling in space. Others are clearly flying untethered from earth. In this body of work, he harkens back to the deep bright pigments he saw in Indian textiles, spices and temples. It was perhaps inevitable that he would branch into other materials once the scale and energy of this constructed paper works found their audience. They were a bridge from Clinton Hill’s work of the 1970s to the final, expansive phase of his career and they are among the most beautiful and beloved works of this life.

V

Entering the 1980s, Clinton Hill was Professor at the City University of New York and had received National Endowment for the Arts grants in 1976-77 and 1980-81. His exhibitions at the Marilyn Pearl Gallery in Midtown were successful and received enthusiastic critical reviews. He was devoted, friendly, generous person whose studio hours went long into the night and knew no particular schedule or limits. The working environment of his studio, filled with finished work, paper and wooden components, works in progress and disparate collections of Asian art, native American baskets and ornaments and work by many friends invited visitors to browse and begin to understand the far-reaching embrace of Hill’s Interests.

Clinton and Allen remodeled a loft on Prince Street in Manhattan’s SOHO district. Working on their loft, they handled pig pieces of plywood, plasterboard, fiberglass and sheets of plastic. Soon Hill began to assemble sheets of wood, dowels and oddly cut geometric elements. He covered them with expressive marks and vivid colors to bring each composition into a coherent whole. Visitors entered Hill and Tran’s loft directly through his studio. It was typically filled with works in progress. It was a generous space with tall windows looking onto Prince Street. Hill loved to hear the sound of voices and traffic as people passed under the windows, bringing the life of the neighborhood into his studio as it always did in his work. His largescale constructions of the 1980s and 1990s exhibit a new dynamic of space and form reminiscent of the city and its unpredictable stream of forms in motion.

Clinton Hill’s familiar long lyrical lines are always present. Now they move between strong countervailing forces. Sharp diagonals bisect the colored planes. Areas of frenetic activity create a musical drumbeat of visual energy. Big bold horizontals hold and steady the ensemble. May of the larger constructions have open areas that bring the wall surface into Hill’s visual discourse. Working around and within a plane of canvas, he painted each surface to reinforce the dynamic interplay of attached three-dimensional elements. These are carefully orchestrated works from an artist who had mastered his repertoire of forms over many years.

Some of Hill’s most elegant and delicately complex works of the 1980s are made of a lowly material, plastic. While building his loft studio and often helping friends do the same, Hill discovered sheets of plastic and vinyl. Clinton and Allen lived above the Ward-Nasse Gallery and frame shop. There, Hill discovered sheets of vinyl in a rainbow of colors. They were light in weight and he could cut them with precision into very thin linear elements. He achieved a sense of near weightlessness and the illusion of flying in this body of work. Hill decided to paint the plastic and vinyl pieces with lightly textured and mottled metallic pigments. These works recall the surfaces of returned space vehicles burnished by the forces of speed, heat and friction. Often small and jewel-like he placed some of them in custom made Plexiglas boxes so that they appear to float in the air.

As the millennium approached, Clinton Hill returned to pure painting filled with his speeding diagonals, loops and spiraling forms. Alternately flat and shaded to evoke deep space, they move and spin in familiar ways. Now the emphasis was on color, glorious color in full bodied saturated planes. Ringing yellows, earthy reds, otherworldly purples and deep blacks create a bright resonance. Most summers, Hill and Tran spent time in the country watching the colors of the earth, flowers and the sky.

These can be found in his paintings of 1998 to 2003. They are often titled for the seasons of the year of particular, fondly-remembered places. Some of his final paintings are grand in scale, full of exuberant energy and bold. Others are intimately scaled and packed with complex forms. Each is a complete world unto itself, yet they are exquisitely complementary to one another and enjoyable to encounter as a group. In them, we experience Clinton Hill’s effortless fluency, personal and free. Like a heartbeat, the steady rhythm of creation in the studio kept him alive. He painted right up to the final weeks of his life. Younger friends could not possibly have known how bright and varied, timely and profound a body of work he created over fifty years. We offer this two gallery survey of Clinton Hill’s work as a preliminary look into and artistic estate notable for its variety, constancy and beauty.